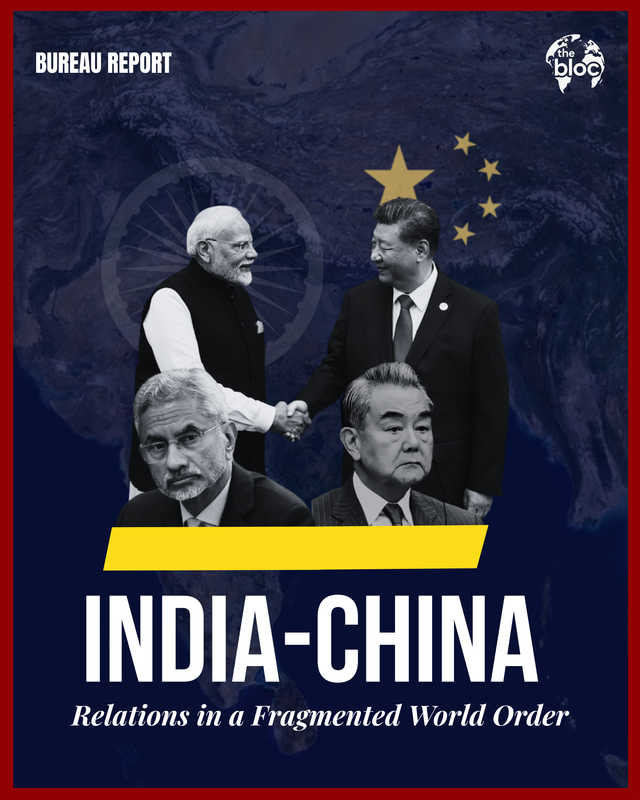

China’s foreign minister Wang Yi is set to visit India on Monday, August 18th, for the Special Representatives dialogue in New Delhi scheduled with his counterpart, EAM Dr. S. Jaishankar and India’s NSA Ajit Doval. This comes right before PM Modi’s visit to China for the SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organisation) Summit. These two parallel developments aren’t just isolated optics but suggest a larger drift from unilateral dependence on the west, towards an increasingly multilateral global order.

Commerce in Conflict

India’s trade numbers in FY 2024 depict a paradox; Commerce with China touched US $118.4 billion, and trade with the U.S. stood at US$129 billion, with India having a $45 billion surplus in goods-trade. However, our largest economic partners have historically been among the least reliable allies. Yet, in today’s world where trade, technology, and capital are leveraged in the churn of geopolitics, dialogue within the realm of fiscal and economic policy becomes not just desirable but, an imperative.

India’s trade surplus with the United States, however, hasn’t been well accepted by the reinstated populist regime. The U.S President, post the initial 25% tariffs, openly acknowledged in a press conference at the White House that “India doesn’t do much business”, softly signalling New Delhi to submit to the MAGA narrative and pry open the floodgates of the world’s largest consumer market for American corporations.

An additional 25% tariffs under the pretext of purchasing Russian oil were imposed as the final straw, for India to restructure its trade and give the U.S. leverage, especially within the dairy and agricultural sectors. New Delhi responded in no submissive manner, openly pointing out hypocrisy over American bilateral-trade and energy dependency on Russia.

While India kept a close eye on the Alaska Summit, The U.S. delegation bound for New Delhi from August 25-29, to negotiate bilateral trade was cancelled immediately after. This indicates that all is not well between the two nations, whereas trade friction with the U.S. has now compelled India to rethink its strategic allies as it chooses to pursue autonomy, or in PM Modi’s doctrine of ‘Aatmanirbharta’, over submission.

This recalibration may well push New Delhi Closer towards China and the BRICS. Although not completely abandoning the West, but as a strategic hedge to preserve leverage and make room for adjustments if Washington continues down the path of economic coercion.

Self-sufficiency; Shanghai and New Delhi

The outcome of populist policies being rolled out by the U.S., has painted the two civilizational states, a larger picture. Both India and China have their economies booming unprecedentedly. India’s GDP grew at 6.5% (FY 2024-25) whereas the Chinese Economy expanded at 5% overall (2024).

For India, this growth comes amid a push for manufacturing under the Production-Linked Incentive schemes, digital public infrastructure, and a stronger focus on energy security.

China, despite external pressure and decoupling trends, has managed to stabilize its economy through domestic consumption, green technology exports, and strategic investments in the Belt and Road Initiative.

Together, this not only reflects economic expansion and self-sufficiency, but a demonstration of geopolitical standing, as both nations are competing to assert greater autonomy and roles in global governance while cautiously building capacity against Western pressure.

If India and China are to deepen their engagement, the effect would be most acutely felt in Washington. For the United States, the simultaneous rise of two economies already complicates its ability to maintain primacy of the dollar, technology, and its security architecture. All while losing India, as a strategic ally in South Asia.

Special Representatives Dialogue; What is expected

While stakes are high, it isn't all smooth when it comes to India-China bilateral relations. There hasn’t been any diplomatic engagement since the Galwan valley clash in Ladakh in 2020. Therefore, the primary aim is to come to a mutual agreement on the recent border disputes and pave the way and agenda for a successful bilateral for the heads of states at the SCO.

Alongside dispute-resolution, crisis-management protocols would have to be restored to avoid miscalculations turning into crises. Reviving dormant mechanisms such as the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination (WMCC), joint military working groups, and regular corps-commander level meetings would reinstate institutional channels that once helped curtail scuffles. These, along with diplomatic hotlines can serve as stabilizers in times of probable escalation.

New Delhi has to opt for a path which helps maintain India’s strategic autonomy. India continues to maintain its diversified partnerships through the Quad, Europe, and the Global South, while it has now seized the opportunity for an ‘interest-based’ engagement with China. This balance allows India to align against overdependence on any bloc while preserving room for pursuing self-interests in a multipolar global order.

Despite lack of common ground, space exists for low-risk and citizen-centric cooperation. Resumption of direct flights, facilitation of the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra, and other symbolic measures which can signal goodwill and build trust, without directly committing to trade or concessions.

Finally, the geopolitical messaging during Wang Yi’s visit must be carefully curated. The dialogue offers New Delhi an opportunity to test conditions and set the tone for higher-level interactions. However, optics must not outpace substance.

India’s objective should remain probing the scope for cooperation without diluting its strategic autonomy.