Once in a while, when I see the marvels of AI and its impact on daily life including facial recognition, generating language, images, I often wonder what level of ‘agency’ can we offer to these systems. I mean recommending food, mopping the floor, doing laborious tasks is all good. But, what if it is given the ‘agency’ to take crucial-high stakes decisions? The pinnacle of agency would be a system that is allowed to govern over all citizens forming a republic of its own. An algorithm asked to form laws that would “restrict” us and press us into a rigid mold.

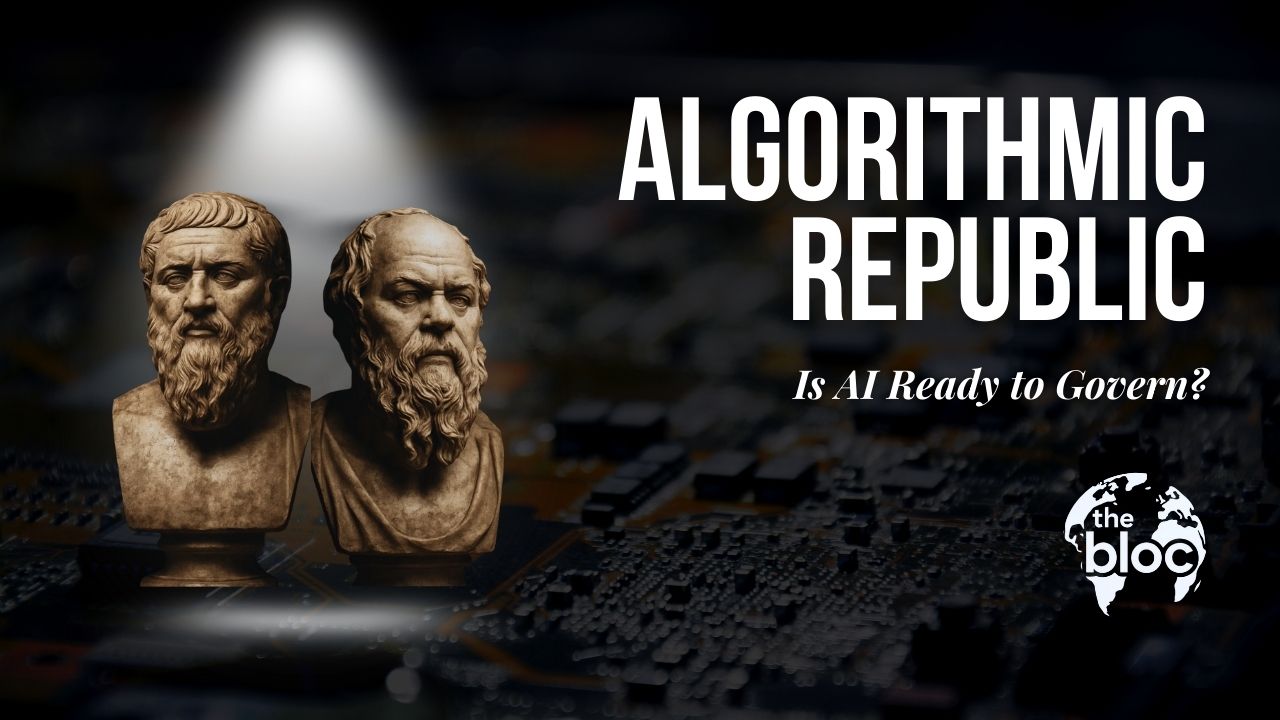

But governance is an ancient preoccupation: who should rule, and how do we choose them? Of course, the question of “who should rule” is hardly new. That question fuels half the dinner-table debates in Indian homes. Which party? What trade-offs? How do we optimize who governs us? These debates are not unique to us Indians, it has been a hot topic of debate amongst many ancient philosophers. Going back to ancient Greece, Plato’s philosophy states in his seminal work ‘The Republic’, the character of Socrates is highly critical of democracy and instead proposes, as an ideal political state, a hierarchical system of three classes: philosopher-kings or guardians who make the decisions, soldiers or "auxiliaries" who protect the society, and producers who create goods and do other work.”

Diving deeper into this philosophy, we are witnessing an emerging era where we would have extremely smart AI agentic systems which claim to be at par with PhDs which literally means “Doctor of Philosophy”. But the question is, should we let these systems govern and make decisions for humans? Are we ready for a society governed autonomously by AI? If not, are these systems even capable of assisting people who govern our societies? In this op-ed piece, I want to zoom in on the “directionality” and “optimization” strategies of decision-making; the messy, subjective side rather than on the objective tasks where AI shines, like pulling facts, building predictions, or crunching data for a single right answer or where the stakes are lower (even though I agree eating good food is a priority).

Here, we are focusing on three different scenarios of governance which include:

1. A society autonomously run by AI systems with no human intervention

2. A society run by humans but heavily assisted by AI systems and

3. A society run by humans with minimal or no intervention by AI.

But before entering the debate and discussion phase we need to better understand how any AI system works, let's dive into the details of its training process. All AI systems are trained heavily on datasets that are available online to give them a broader understanding of the language and further tuned using a reward based system (much like Pavlovian conditioning) to be responsible and to be “politically correct”. Most of the time you would notice, AI models refrain from answering controversial questions and further nudge you to ask more “sane” questions. This forms the building block for a large language model without “intuitive” reasoning abilities (think GPT-4o).

But, this training paradigm has advanced further. With the introduction of “reasoning” models, each model, just like humans, forms a chain of thought based on the requirements, end goals and constraints to reason for every question and as it walks down that reasoning chain, it optimises further to arrive at the answer making the answer “optimal” for the given query. For the sake of better visualisation, think of the o3 reasoning model by OpenAI. Now, ‘often’ this works very well for mathematical reasoning tasks and other fact based questions which have only one correct answer. But for governance, it takes a completely different turn.

Governance often has to balance the interests of many different groups in society. There is rarely a single “right” answer; instead, decisions are guided by the moral philosophy of those in power and by what best aligns with the values of the majority. In simple terms, think of governance as facing a question with many possible answers, you must choose the one that resonates most with your people’s sense of morality. That’s not an easy task.

AI systems, in a sense, reason in a similar way. Trained on vast amounts of data, they learn to weigh possibilities, consider who is affected, and optimize outcomes. It’s tempting to imagine simply handing such decision-making over to AI. But there’s a catch: AI systems also absorb the biases present in the data they are trained on which can lead to decision making biased against a racial, ethnic, gender or any other marginalized communities. We may correct some of these biases, but that raises a deeper question, are all biases necessarily harmful? or are some simply reflections of cultural or moral differences? For example, an example of a good bias is to take into account the ethnicity of a patient before medical diagnosis or using age as an important deciding factor for recommendation systems. If bias can be “good” or “bad,” then what principle helps us decide which ones we keep and which ones we reject while making a decision? That principle is fairness.

What does it mean for a society or an algorithm to be fair? Philosophers offer different answers. A Rawlsian view treats fairness as strict equality: everyone must be treated the same. A utilitarian perspective, on the other hand, sees fairness in terms of maximizing overall benefit, even if it means some inequality. From your point of view, fairness can mean strict equality (an egalitarian view) or maximizing overall benefit (a utilitarian view). But in practice, fairness rarely fits neatly into any one philosophy it shifts with culture, values, and lived experience.

To see how this plays out, consider a country facing a critical choice. On one side, there’s an international AI race demanding massive investment in technology. On the other, rising border tensions call for urgent spending on defense. Which way should the government lean? If you choose defense, you protect sovereignty but risk falling behind in AI innovation. If you choose AI, you may compromise security in the present. Notice how the “direction” of your choice depends not on a formula, but on your own moral compass—your sense of what should matter more, here and now. As you may have noticed here though, the direction of your decision is not completely binary, there are often layers and shifting weights to your decisions. Maybe you decide to split resources, 60% to defense and 40% to AI. But that split isn’t math; it’s a reflection of your moral compass and figuring that out is the hardest part.

Given the context of decision making, the big question is “What is the moral compass of an AI system?”. A lot of research recently has focused on finding the “direction” of AI systems in many different scenarios of decision making. Many researchers study the reward based systems used to tune these models and make them politically correct. Often these also reflect the biases the model adheres to where it might get rewarded more for keeping the bias into account in their decision making process. So understanding the moral compass and biases of an AI system is quintessential to understanding how an AI model finally arrives at a decision for the given situation.

Measurable skews have been observed in AI models in many recent publications with biases emerging politically (often mildly liberal), culturally (Western-centric defaults even in non-Western contexts), and ethically (a safety-trained omission bias that over-prefers inaction or “no” in thorny dilemmas). Some providers have nudged newer models closer to center, but perfect neutrality is a unicorn. In summary, today’s models can reason about ethics, but they do it through a particular lens.

However, a natural question arises here: biases are prevalent in humans as well and we still trust them. Why not AI? The answer, I believe, lies in accountability. Humans are responsible for their actions—AI systems are not. Take the case of a hospital. As a patient, I would still choose a human doctor over an AI, even if the AI boasted 99% accuracy (though the statistician in me protests). Why? Because the “human touch” carries with it the comfort of accountability. A doctor is answerable for their decisions and, crucially, has the capacity to recognize and correct mistakes. Humans possess self-reflection, the ability to step back and evaluate their own actions. That capacity reassures us that errors can be acknowledged and fixed. AI, by contrast, is still a black box; difficult to interpret, harder to debug, and lacking anything close to a conscience. Until systems can meaningfully self-reflect, trusting them the way we trust people will remain a leap too far.

But let’s assume for a moment that models are arriving at the right conclusions that would exactly mirror the decisions taken by the governing body and this is all we care about. What then becomes the bottleneck? The danger lies in their latent ability to be deeply persuasive. It’s like using the wrong method to reach the right answer: the outcome looks fine, but the reasoning is flawed. And persuasiveness without conscience is terrifying. Since these models are so well adapted to reasoning tasks, just like lawyers, they possess the capability to logically convince people of the correctness of their answer without us ever understanding the intent behind the decision.

Consider a classroom. A teacher solves a few problems and asks the student to learn. The student can either adopt the teacher’s method and apply it to harder problems or simply persuade the teacher that their own (incorrect) method is valid. Here the line between factuality and persuasion blurs. Without conscience and ethical grounding, persuasion often wins out, especially when the problem is complex.

Ethical decision-making, in practice, often comes down to persuading others that your choice is justified. But in human settings, the agency and accountability rests with the person in charge. If we hand that agency to AI, we risk decisions shaped not by a conscience but by the persuasive techniques of a black box. At best, the model mirrors the moral system of its creators (the unseen “Pavlovs” behind the scenes) whom we may not trust to govern the masses.

Therefore, the idea of a fully autonomous AI system is one we should not adopt. At the same time, dismissing AI altogether would be equally shortsighted. Any powerful tool when used responsibly has the potential to transform society at macro and micro levels. So, the real opportunity lies in harnessing its strengths under human oversight. However, with assistive technology we need to make sure AI becomes a good advisor rather than a “yes man” while also being factually correct. Without these two, we can’t trust these systems as advisors as well. But, what most people do not realise is the immense potential of such systems in assisting governance by drawing simulations. Yes, it is not perfect and it is very very hard to perfectly map AI systems to human behaviour, but even coarse approximations can also add a lot of insight. This can reduce “agency” per say by leaving decision making to humans while adding extra dimensions to the decision making process.

Imagine designing AI systems with diverse but well-defined ideologies and biases. By simulating how each system evaluates the same dilemma, we could explore the consequences of different moral frameworks and identify policies that align best with our collective values.

In this way, AI becomes not a replacement for human judgment but a tool to expand it. The challenge, then, is to establish clear and uniform guidelines for how AI should be integrated into governance and policy-making. Without such guardrails, the promise of AI in decision-making risks turning into peril.

Oof, after reading so much jargon one might be frustrated with so much negativity. So, let's reward ourselves with something positive. How can we actually use AI as assistive systems in “governance”? Given so many problems, don’t feel overwhelmed and to start off let’s keep it simple.

Be clear about the role and agency given to AI systems, check who could be helped or harmed, publish a one-page “fact sheet” for each system (purpose, data, limits, test results) because largely a model’s choices are driven by its training processes, put a named human in charge, and give people a real way to appeal.

All these rules and checks should be baked into vendor contracts (where the data came from, how it was tested, when it gets switched off). Tests should be performed before launch for fairness and obvious mistakes, with continuous testing after launch with regular check-ups and public updates. As engineers, we need to learn from what works (Finland’s AuroraAI, Estonia’s Bürokratt, Singapore’s Ask Jamie) and what doesn't (Australia’s Robodebt, Netherlands’ SyRI). Additionally, the models need to understand local values, cultural nuances. Engineers can write simple “house rules” for the model, let users opt out, and be open about trade-offs because “neutral” AI doesn’t exist, so let's make it “transparent” to account for each decision made by the model!

At last, we have made it to the end of a very long yet hopefully insightful journey and I thank you for your patience. I hope this article and my arguments sparked an internal dialogue with your own conscience. Keep in mind, I am no oracle, and I might have flaws in my philosophies as well. If it enraged, intrigued or simply confused you; good! At least I was able to start a conversation, which leads to better discussions, arguments. As a society, this is how we optimize our decision making :).