In October 1928, Punjab’s political climate was shaken when Lala Lajpat Rai led a protest against the Simon Commission in Lahore. The demonstration was met with a brutal police lathi charge that left Rai grievously injured. He died on 17 November that year, his death widely attributed to the excessive force used by the police. The young revolutionaries of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association, most notably Bhagat Singh, were deeply moved by Rai’s death. On 17 December 1928, Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev assassinated Assistant Superintendent J. P. Saunders in Lahore, explicitly framing the act as retribution for Rai’s killing.

Rai was not only a national leader but also associated with the Hindu Mahasabha, an organisation that emerged to give political articulation to Hindu interests in the early twentieth century. The Mahasabha became a channel through which the ideas of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar entered the nationalist and cultural space. By the 1920s, Savarkar had already articulated his vision of Hindutva. His writings, particularly his interpretation of the 1857 uprising as a war of independence, inspired a generation of thinkers and activists. Bhagat Singh himself read Savarkar’s history of 1857 while in prison. Though Singh’s socialism and internationalist outlook diverged from Savarkar’s Hindutva, the imagery of sacrifice and armed resistance in Savarkar’s work resonated with his revolutionary sensibilities. This shows how Savarkar’s ideas could influence even those who critiqued or moved beyond his ideological framework.

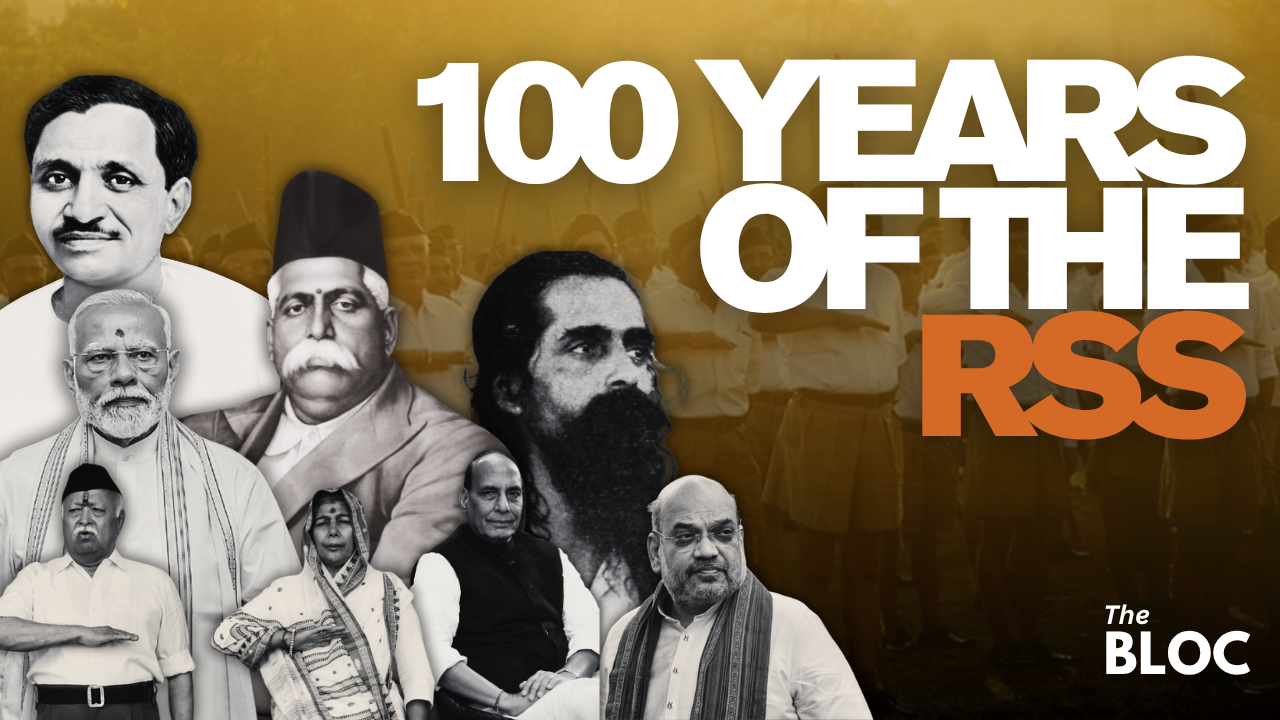

For the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, founded in 1925 by K. B. Hedgewar in Nagpur, Savarkar’s influence was more structural. Hedgewar and the early RSS leadership absorbed the belief that Hindu society needed to consolidate itself as a cultural nation. While the Hindu Mahasabha moved toward electoral politics, the RSS focused on grassroots mobilisation, creating a model of daily shakhas that fostered discipline, community, and a sense of collective identity. M. S. Golwalkar, Hedgewar’s successor, deepened this framework.

In his work Bunch of Thoughts, Golwalkar affirmed the principle of equal citizenship, writing that “in secular life all citizens are equal; this principle should be strictly adhered to.”

His statement highlighted that the organisation’s intellectual framework included civic equality as a foundational value. Yet the RSS is too often reduced in public debate to its political role. Such a reading misses its wider character as a civil society network. The Sangh family runs an extensive ecosystem of institutions: schools, vocational centres, relief programmes, and healthcare camps. Vidya Bharati, for instance, manages thousands of schools and educates millions of children, representing a sustained investment in curriculum and teacher training. Seva Bharati works in disaster relief, rehabilitation, public health, and special-needs education. These activities function as service work, rooted in social welfare and capacity building rather than immediate electoral return.

Sustaining this ecosystem are the pracharaks, full-time organisers who often renounce family life to dedicate themselves to community work and institution building. Their model of lifelong service underlines how much of the Sangh’s energy is invested in grassroots social labour. At the same time, the Sangh’s expansion has been uneven. States such as Kerala resisted large-scale growth for long periods, showing the organisation’s structural limits. Today, outreach to urban youth and diverse social groups demands modern communication strategies and new forms of civic engagement. Institutional depth alone is not enough if methods remain outdated.

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh is often seen as rigid and uniform, yet Mohan Bhagwat’s 2023 remarks on LGBTQ+ rights reveal a different side. Acknowledging sexual orientation as biological, he stressed that LGBTQ+ individuals deserve private and social space, a statement that surprised many and hinted at an inclusive strand within the Sangh.

Such moments expose the internal pluralism often overlooked by critics. While deeply rooted in tradition, the RSS can diverge from public perception and even government policy, showing flexibility in its social vision. These instances suggest that the Sangh is not simply a monolithic force of conservatism but an organization capable of debate, reflection, and measured evolution. This further reconfirms the emergence of a liberal-right political current, long visible in the United States and now gaining traction in India. Figures and movements willing to combine conservative cultural frameworks with socially inclusive positions may represent a new strand of influence in global and Indian politics, appealing to constituencies that value both tradition and individual rights.

Understanding the RSS through this lens challenges simplistic portrayals. Its influence extends beyond politics into society, education, and culture, and acknowledging its ideological diversity is key to appreciating its broader role in contemporary India.

Taken together, these elements reveal the RSS as a social movement first and a political influence second. Its strengths lie in institution building and volunteerism; its challenges lie in regional variation and the need to modernise for a plural, technology-driven public sphere. If it seeks lasting relevance, the Sangh will have to adapt its methods while retaining its social commitment, ensuring that civic service, education, and local organisation remain at the core of its public presence.

In the end, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh must be understood not merely as a shadow of political power but as one of the most enduring experiments in social organisation in modern India. Its history shows that its influence stems less from momentary electoral gains and more from decades of patient institution building, cultural work, and disciplined volunteerism. Yet, its future depends on whether it can evolve beyond the structures of its past. In an India that is younger, more urban, digitally connected, and increasingly plural, the Sangh’s real test will be whether it can combine tradition with innovation, upholding its ethos of service while speaking to new generations in new languages. If it succeeds, its role will remain not only politically consequential but also socially transformative.